This tale comes from Transylvania, a region I’m deeply connected to through my mother and grandmother, aunties, uncles, and cousins. I spent my childhood holidays there, weaving together a beautiful tapestry of memories. I think it’s destiny that no matter where I live and work in the world, my family threads draw me back to this place that has come to define me.

So today’s story is about family memories and also glimpses into the history of Transylvania, both inspired by strudel. Every time I write about strudels, I remember what Elisabeth Luard wrote in her book European Peasant Cookery that the journey of strudel in Europe started when ’the Turkish pastry chef met the German housewife’.

In a region like Transylvania, where both the Ottoman and Habsburg empires ruled in turns or shared a border, these influences have fused into the variety of recipes we know today.

Strudel’s parents

Until the Ottomans perfected the filo technique from the Greek and Armenian bakers and brought it here to Central and Eastern Europe, this kind of filled roll was made with yeasted dough.

In old German, the word means ‘whirlpool’, describing the layers that swirl together, hypnotising you into a sweet trance. Anything that’s rolled into a log, provided it uses a sweet or savoury dough, can be a strudel. On the other hand, filo means ’leaf’ in ancient Greek because the dough was as thin as a leaf, and also because many breads and pies were baked on leaves instead of sheets or tins.

In my family, we only knew the filo strudel. It is also called retes if you are a Transylvanian-Hungarian or plăcintă if you are in a Transylvanian-Romanian home, or strudel if you are at a Transylvanian-Swabian table. Generally, we call it ștrudel all over the country, and it has always been my favourite snack. I have fond memories

of preparing it with my grandmother, stretching and pulling the pastry over the dining table.

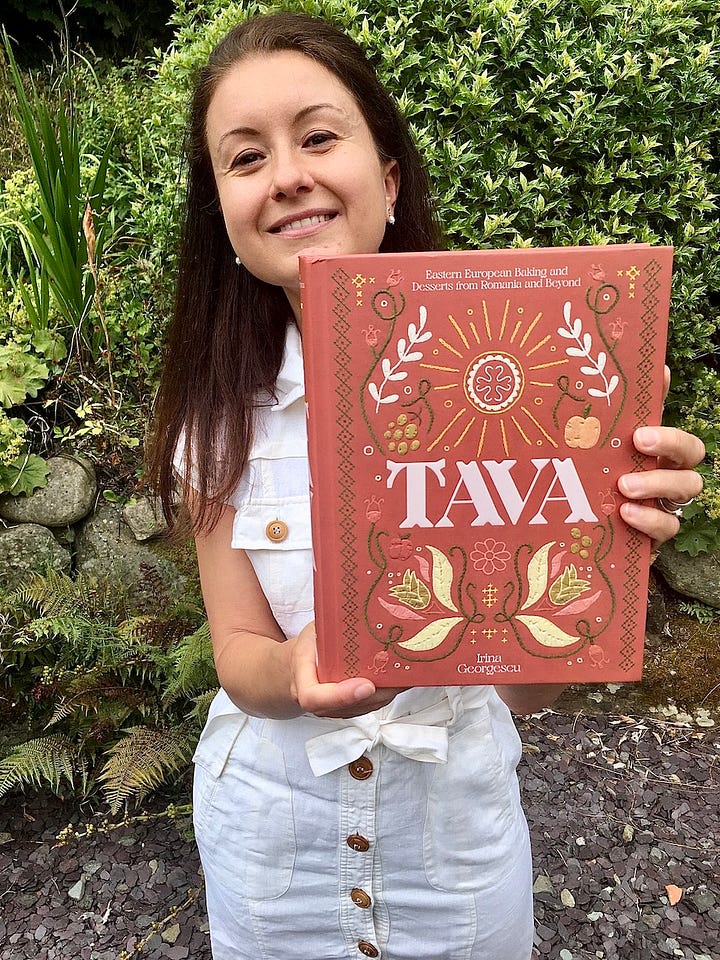

In my Eastern European baking book, Tava, I offer two different filo recipes, one of which is intriguingly made with butter. If you keep this warm and relaxed, it will stretch beautifully. My favourite seasonal summer strudel, the one I learned from my grandmother, is with sour cherry: sharp and intense, the sweetness coming mainly from the dusting with icing sugar. Then, in the autumn, my favourite strudel is with pumpkin, which was also my mum’s favourite: it’s jammy, naturally sweet and oozing at the edges.

Eastern European big strudel family

The second story about strudel comes from Banat in southwest Transylvania, from our Swabian communities called șvabi. Here, a strudel can also be made with yeasted dough, like in the recipe below. It’s called Mohnstrudel aus Hefemurbeteig, which means a poppyseed strudel with yeasted shortcrust. You will find this type of recipe in all countries that were once under the Hapsburg Empire, under different names, such as Potica for Serbians, Makovnjača for Croatians, Beigli of Kindli for Jewish-Hungarians, Makivnyk for Ukrainians, Makový závin for Czechs and strudel or cozonac cu mac in Romanian.

I’m curious to know what it is called in your region or country.

Swabian strudel days

Swabians liked to have Strudel days, when they served it as a main course rather than a snack or dessert, typically following a soup. In German culture, lunch is the main meal of the day, so having chicken soup with noodles (which often were made from the trimmings of the strudel pastry) and then a couple of savoury and sweet strudels, filo or dough, would have been quite a feast.

If the strudel was not soft enough, women used to say that it was baked: ‘unter’m Mondlicht’, which means ‘under the moonlight’. Hopefully, mine and yours (if you make the recipe) will get their approval.

Poppyseed strudel recipe

Ingredients:

250g plain flour

40g caster sugar

7g dried yeast

Pinch of salt

40ml double cream

2 medium size eggs

75g unsalted butter, grated

Filling:

150g ground poppyseeds

50g caster sugar

20g almond meal or plain flour

60g unsalted butter, cut into cubes and soft

1 medium size egg

1tsp vanilla extract or rum

Egg wash: 1 egg yolk mixed with 1 tbsp cold water.

Method

Prepare the pastry by hand or begin with a food processor. Start by combining all ingredients, except the butter, to create a rough dough. Knead it briefly, then incorporate the butter. If using a food processor, pulse three times, then transfer the dough to a lightly floured surface and knead briefly until smooth. It may become a bit sticky, which is fine. Set it in a bowl and cover with a plate, allowing it to sit at room temperature (18-20°C) for 45 minutes. This is not the type of dough that will double in size. Afterwards, refrigerate it for about an hour to firm up just enough to be able to roll it.

You can make it a day in advance, but it will be too firm to use directly from the fridge, so you’ll need to let it sit at room temperature for an hour before using it.

Meanwhile, prepare the filling by mixing all the ingredients in a food processor. Keep it at room temperature so it is easily spreadable.

Dust the work surface and dough lightly with flour, then roll it out into an approximately 30x40cm rectangle. Distribute the poppyseed filling evenly, leaving a small border around the edges. Starting from the longer side, roll it into a log and tuck the ends underneath, pressing on them slightly (it needs to fit onto your baking sheet). Don’t roll it too tightly, but not too loosely either; just allow a little room for expansion. Place the log seam side down on a lined baking sheet, then brush the surface thoroughly with egg wash. Use a sharp knife to make small cuts along the sides to allow the steam to escape.

Place the strudel in the fridge for 10 minutes or until the oven heats up.

Preheat the oven to 200°C. Bake the strudel for 25 minutes, lowering the temperature to 180°C after the first 15 minutes. It should be a deep golden brown. Place it on a cooling rack and cover it with a cotton towel. Slice it only when it has cooled; it will keep for 2-3 days, but it’s best on the same day you baked it.

Tip to use it up: warm some slices in a small pan with milk. It’s easier than making a bread and butter pudding.

Poftă bună. Enjoy.

Since I mentioned Elisabeth Luard at the top of this e-newsletter, you can enjoy more of her wonderful writing by following her substack posts here. As you know, she is also an extraordinary illustrator, and I have bought many of her watercolours here.

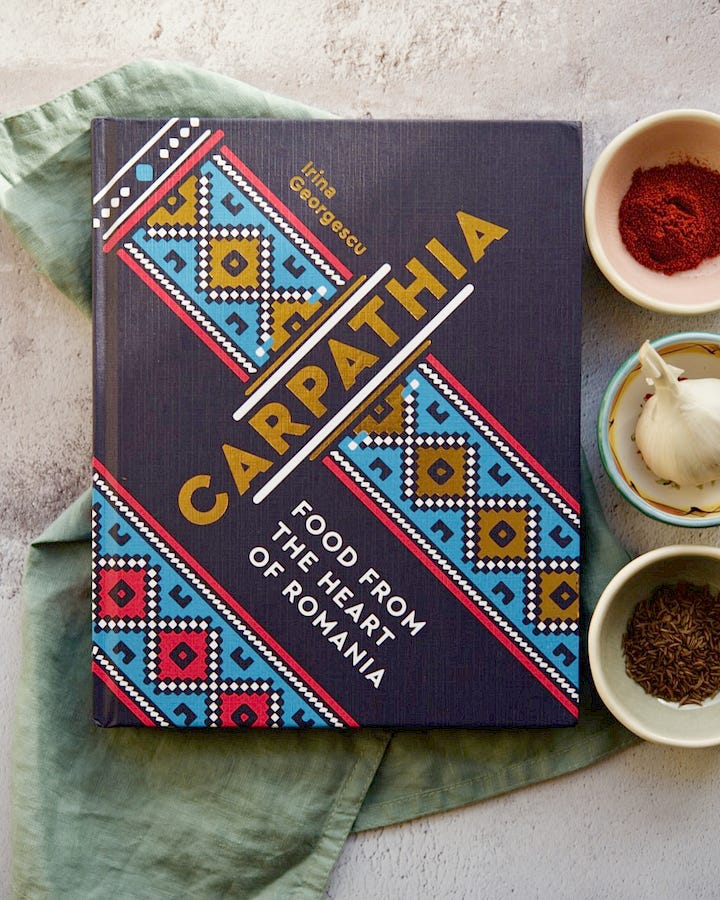

My books for Christmas

I know you know, but just to remind you, my two books make a good Christmas present for a foodie friend who also likes travelling and cooking.

Carpathia link here and Tava link here. Of course, I can also send you a signed copy (UK only), just get in touch. If you’d like to travel to Transylvania with me on a culinary tour, you can read the details here.

I love poppy seed sweets and I love food name etymology.

Thank you for the strudel journey.

And it makes perfect sense that Romania would have the most strudel styles of anywhere.

Beautiful! There's a strudel-stretching situation in the Christmas traditions of Provence, an apple pie, croustade, that's topped with rumpled-up strudel-pastry, like an ummade bed. It's sold in farmer's markets as the centerpiece for the Treize Desserts - an arrangement of sweet things (12 apostles plus Jesus) laid out on a table throughout the holiday for people to help themselves - as I'm sure you already know! Is there a similar Christmas arrangement in Romania? Seems to be quite localised in France.