Cozonac is Romania's iconic festive bread, traditionally made for Christmas and Easter, usually shaped into a rectangular braided loaf. The most popular filling is made with walnuts (and rum), but people also love to use poppy seeds or Turkish delight.

The dough, enriched with butter, milk and eggs, is infused with the subtle flavours of lemon zest and vanilla, filling homes and bakeries with a glorious aroma as it comes out of the oven. We often serve it with a cup of coffee or a glass of cold milk in the morning, or for dessert after Christmas lunch.

Baby in a cradle

If you read my post from last week (see here) and saw this subtitle, you must be thinking that we are obsessed with babies and baking in Romania. It’s because Christmas is a celebration of the birth of Jesus, and we are reminded of it in traditional recipes. One of the explanations for the word ‘cozonac’ comes from the Romanian food historian Simona Lazăr, who traces it back to the Greek kosona, meaning a cocoon, a baby protected by the cosy, safe world of the cradle. Many ritualistic breads were, in ancient times, abstractions of a human shape. Even today, some breads (including gingerbread men) are shaped with a head, arms and legs, whereas others, like cozonac, symbolise a body snugly wrapped in dough swaddles.

The baking superstitions surrounding Cozonac

No matter how many superstitions you might know about baking a cozonac, you are bound to miss one, and the whole thing will be ruined. This, in itself, is one of the superstitions, so please just bake the recipe, and everything will be fine.

Every family has its own ritual, and here is my Mum’s:

6:30 am: Mum would wake up at this hour, while the apartment was still quiet, to prepare the starter dough called "maia.” An old tradition stated that the flour should be sifted in total silence and on an empty stomach before sunrise. Everything in the kitchen needed to be spotless, from the work surface, utensils and bowls to fresh tea towels and aprons.

7:30 am: she would combine this starter with the rest of the ingredients, which she had already weighed the night before and left out to come to room temperature.

7:45 am: next, the kneading started. It was done by hand in a large enamel bowl, known as ‘lighean’, which was big enough to wash a baby in. Mum typically prepared 5-6 cozonaci, and the amounts were huge for kneading by hand.

8:15 am: after half an hour of kneading, it was time to add the melted butter, bit by bit, incorporating well after each addition until the dough turned silky and elastic. Mum would tuck her hands under the dough and massage the butter into it, and then, at just the right moment, lift the dough up in the air and slap it back down in the centre of the bowl. Then repeat. At this stage, someone needed to be in charge of holding the bowl in place, so it didn’t fly towards the ceiling.

That someone was me! I used to volunteer every year to help, waking up just before 8 a.m. to join her. A carefree child was considered a good omen for the cozonac to be a success.

8:40 am: the dough was finally allowed to rest, covered with blankets and placed on top of a cupboard in the kitchen. The room had to be kept very warm, as there was no reliable central heating in those days, so we used to turn on the oven and leave the door open. Then, close the kitchen door and try to forget all about cozonac.

Now it’s time to follow the most important unwritten rules:

No one was permitted in the kitchen, as even opening the door could let in ‘the draft’. What is a ‘draft’, known as ‘curent’, in Romania? Well, one writer called it ‘the Romanian silent killer’ :-) It’s quite funny…and true. I hate the draft and keep all the doors closed in the house. Read here.

Loud noises were also prohibited, and conversations had to be whispered. No phone calls. Naturally, looking in to check on the dough was completely out of the question.

“Don’t disturb it,” Mum used to say, “and don’t praise it, either”—if, by chance, my sister and I caught a glimpse of it, seeing it rising nicely. A word of praise or a moan would have brought the curse of the evil eye upon it, and the cozonac would deflate.

10:30 am: time to divide the dough and shape the loaves, then carefully place them in the baking tins. Then allowed to proof for another hour or so, and finally bake.

1:30pm: Fresh out of the oven, the cozonac was nice and soft, and smelled fantastic:

The blessing: before slicing it, you’d need to make the sign of the cross above it three times.

Leave a comment with the superstitions you follow in your home when baking cozonac:

Cozonac, the recipe

Ingredients:

Makes 2 medium loaves

600 g (1 lb 5 oz/5 cups) strong bread flour

14 g (2 sachets) fast-action dried yeast

200 ml (7 fl oz/scant 1 cup) full-fat milk, warmed

2 medium eggs, plus 2 yolks (reserve whites for filling)

150 g (5 oz/genrous 2⁄3 cup) golden caster (superfine) sugar

1 tablespoon vanilla extract

150 g (5 oz/2⁄3 cup) sour cream, at room temperature

grated zest of 1 large orange

80 g (3 oz) unsalted butter, melted

sunflower oil, for greasing

For the filling

150 g (5 oz/11⁄2 cups) walnuts 150 g (5 oz/11⁄4 cups) sultanas (light golden raisins)

2 egg whites

75 g (21⁄2 oz/1⁄3 cup) caster (superfine) sugar

1 tablespoon milk

1 tablespoon orange blossom water

For the glaze

1 small egg, beaten

My method:

In a large bowl or a stand mixer equipped with the paddle attachment, combine the flour and yeast. Next, add the warmed milk and mix until well incorporated.

In a separate bowl, beat the eggs and yolks with the sugar and vanilla until foamy, then mix in the sour cream and orange zest. Use a wooden spoon or the mixer to incorporate this into the flour mixture. Beat on medium speed for 5–8 minutes until thick strands of dough begin to separate. Start adding the butter, one tablespoon at a time, incorporating it well after each addition. At this stage, you can switch to a dough hook or knead by hand until the dough is smooth and comes away from the sides of the bowl. Transfer the dough to a greased bowl. Cover and let it rest for 1⁄2 hours in a warm place.

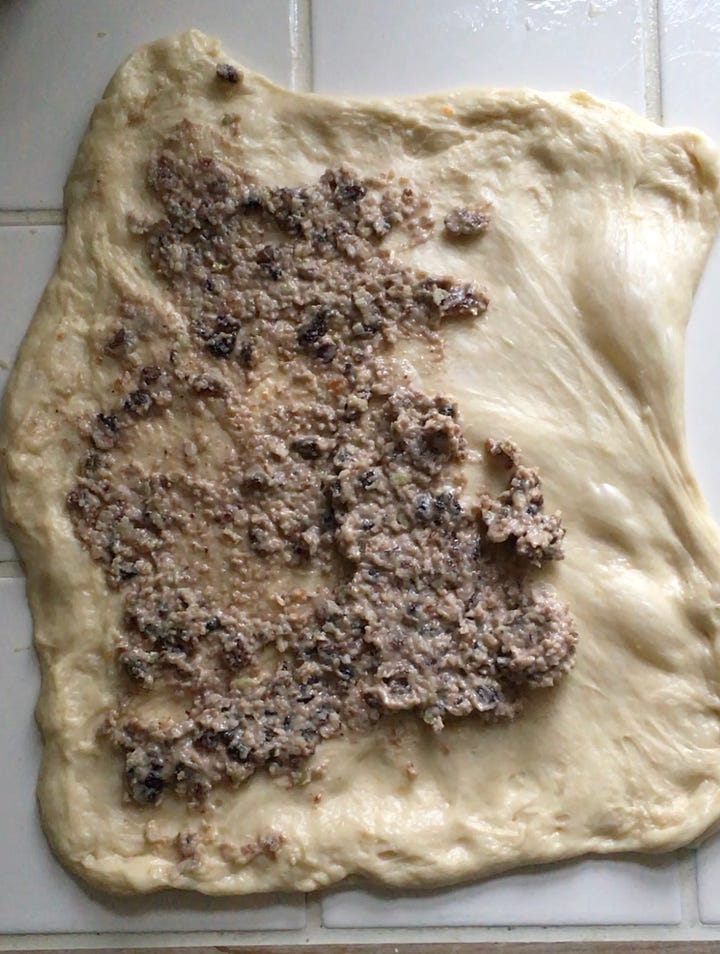

Meanwhile, make the filling by blending the walnuts and sultanas together in a food processor. Add the milk and the orange blossom water and mix well. In a separate bowl, beat the egg whites with the sugar to stiff peaks, then combine with the walnut mixture. Set aside.

Grease and line two 10 x 21 cm (4 x 81⁄4 in) loaf tins (pans).

Turn the dough onto a lightly oiled work surface, shape it into a log and divide into 4 equal parts. Gently stretch and roll one part to the length of the tin and double its width. Spread with a quarter of the filling mixture and roll it up into a log. Repeat with the second piece of dough, then twist them together, tucking the ends in, if necessary. Place in the tin. Repeat with the other pieces of dough and place in the second tin. Cover and leave to prove for 30 minutes in a warm place.

Meanwhile, preheat the oven to 180°C (non-fan)/350°F/gas 4.

Brush the breads with the beaten egg. Bake on the lower shelf of the oven for 20 minutes, then reduce the temperature to 160°C (non- fan)/320°F/gas 2 and bake for a further 30 minutes until an inserted skewer comes out clean. Cover the tops with foil if they turn too dark.

Leave to cool in the tin, covered with a cloth, for 10 minutes, then remove to a wire rack to cool completely, still covered with a cloth.

Recipe variations

People usually add milk to the dough mixture, but some prefer to mix it with sour cream, called ‘smântână’, for an extra soft crumb. The filling also varies from one family recipe to another or by region. I grew up with cozonac made with walnut paste, golden raisins soaked in rum, egg whites and cocoa powder. Other people only had a cozonac with poppyseed filling made by boiling the seeds with milk, although I also have a recipe with butter here. Turkish delight also features in many recipes, which is very intriguing. Shape wise, a cozonac is usually a tall loaf, but in some parts of Transylvania can also be rolled like a strudel, see my previous story about it here.

A nosey neighbour

If I look at Romania’s neighbours and their Christmas or more famous baking recipes, I find the Polish and Ukrainian Jewish babka similar. Yet, babka and cozonac have distinct differences: cozonac contains more eggs, is a taller loaf, and has less filling than a babka. Also, we never pour syrup over cozonac. Then, I look at our neighbours in the south. Bulgarians bake ‘kozunak’ for Easter, which is made with dried fruit or left plain, and the loaf is more intricately braided. Their kozunak is like a Greek ‘tsoureki’, which is traditionally left plain, sprinkled with sesame seeds, and served with red-dyed eggs at Easter.

What worries me about traditional recipes is that we tend to associate them with their more famous peers. Even in Romania, we describe a cozonac as a Romanian babka. Food52 makes something that doesn’t resemble a babka at all and calls it ‘Babka but speedier’ just because it is something rolled with a chocolate filling.

By doing so, we are gradually yet inexorably contributing to the extinction of the culinary identities of lesser-known cultures.

Cozonac in the spotlight: The New York Times and Channel 4

I had the pleasure of working with the team at The New York Times to publish a recipe for cozonac. You can find it here.

In the UK, I was invited by Channel 4 to prepare three Romanian recipes for the presenters and guests: I baked pumpkin strudel, curd cheese brioche buns, and cozonac. Everyone chose cozonac as their favourite recipe.

So if you decide to bake it for Christmas, you know it’s not just a recipe, it’s a famous cozonac as seen on TV.

Just kidding.

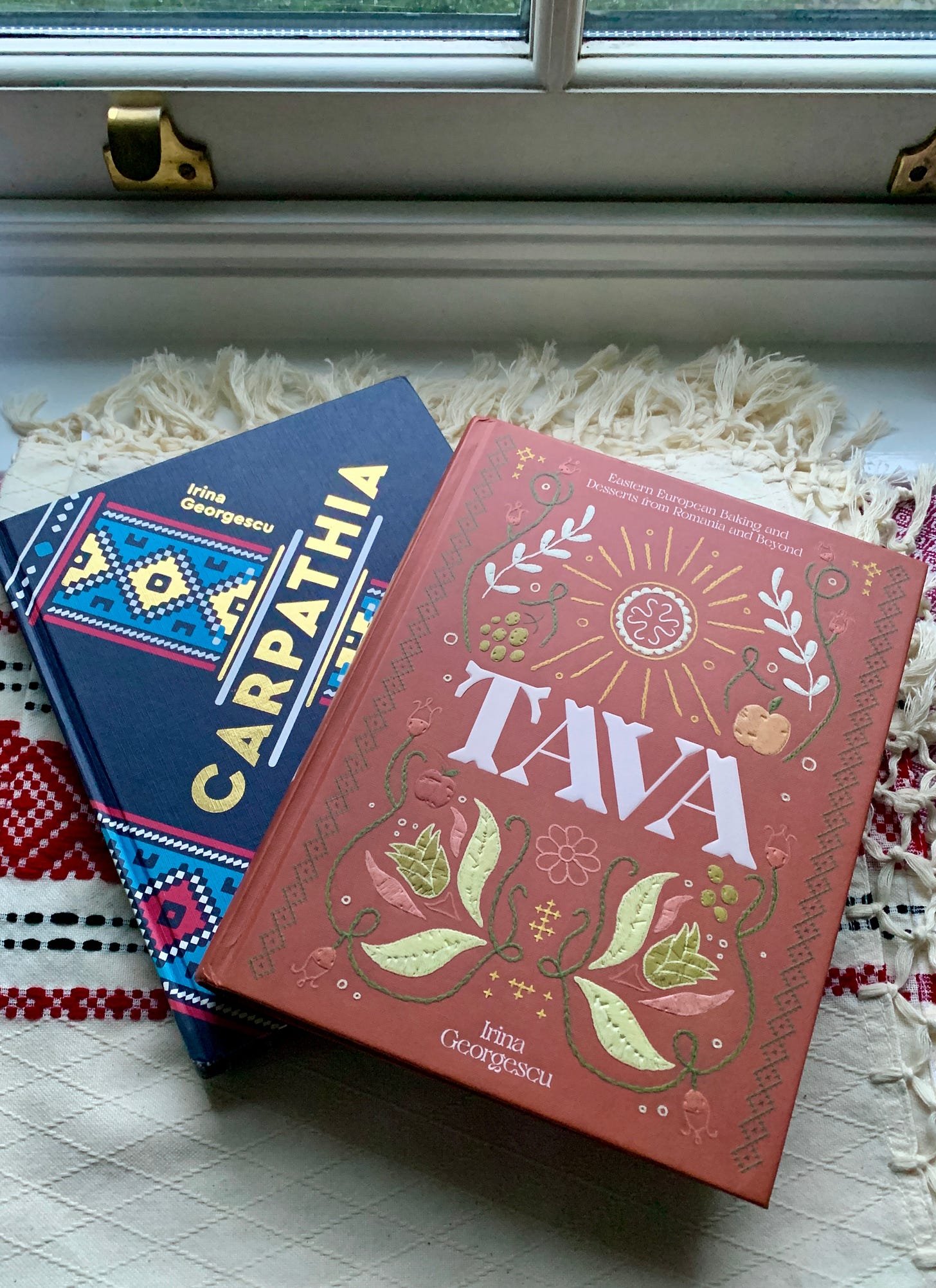

As always, I would appreciate your support by subscribing to and sharing my posts with your friends. It’s free. Also, don’t forget about these two books, which will satisfy your thirst for knowledge.

My mother was Austrian and my father from Romania. We ate this type of sweet bread fairly often and always at the holidays. My mother called it zopfbrot which translates to braid bread. Setimes she baked it in a bundt form. It is beyond delicious and I miss it, as I have only made a few times in my more ambitious years. I am just not a bread baker. I also love and devour bread. It's good to know yourself and your weaknesses. She also sometimes filled it with poppyseeds. So good. Not too sweet. My father always helped with the dough making. He held the huge bowl in his lap and I helped hold the bowl down as he beat the dough with a large wooded spoon. I can still hear how that noise sounded like someone knocking at the door. I have a dough hook on my kitchenaid and I might just give this recipe a try soon. Thank you for the fond memories! Happy Holidays!

Absolutely loved reading these superstitions and rituals. Kozunak is also commonly filled with Turkish delight (lokum) in Bulgaria, but I much prefer it with dried fruit.